Free the streams of Tricity!

In the autumn of 2024, I took part in the Turning the Tide programme, which focused on creatively tackling climate change challenges in coastal cities.

In the “Free the Streams of Tricity!” project, I presented creative visions for the renaturalization of our local stream in Sopot, Poland. Through guided walks, creative workshops, and animations, the project highlighted need to restore and these streams and bring them back to the daylight, while reconnecting our community with nature. By blending art with environmental advocacy, my aim was to inspire a deeper appreciation for the streams that shape our cities.

A special thank you to Koło Sopockie Potoki and mr. Włodzimierz Śliwiński for his help with organising the guided walk.

Place – Fields near the clinic in Brodwino

Place 01 – Park near Obodrzyńców street

In the context of the threats and challenges related to the climate crisis in cities located by the water, I am particularly moved by the way in which streams flowing into the sea are managed and subordinated to the urban infrastructure. An example is Sopot – it has 11 streams flowing through it, most of which are canalized in the urban section. Not many inhabitants and visitors know that there is a stream flowing directly under the famous promenade on Monte Cassino Street. The name of another stream, Kamienny Potok, gave its name to the entire Sopot district, even though it is now almost completely hidden underground.

Kamienny Potok stream

There are several reasons for concreting coastal streams – for example, obtaining space for urban infrastructure and recreational and service space, limiting periodic water pollution at the mouths of rivers to the sea during heavy rainfall. However, during the deepening climate crisis, exposing such places and restoring the riverbed to its natural state brings many benefits.

The practice of exposing streams to daylight is called “Daylighting.” It creates a habitat for wildlife and a place where people can commune with nature. By exposing the riverbed, the city is better able to manage storm water runoff. Such an area also helps reduce carbon dioxide emissions and provides cooling on hot days. In addition to the practical benefits, an important aspect is the revival of historical and cultural connections to water in the area. (Source)

1. Guided walk

along Kamienny Potok

2. Workshops

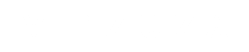

on the topic of our relationship with water in the city + creative workshops about daylighting parts of the stream

3. Animation

an immersive vision of the renaturalization of Kamienny Potok.

The aim of the walk was to take a closer look at our local streams, especially those that have been largely hidden underground due to the development of the city. During this meeting, a group of participants walked along the Kamienny Potok stream, reaching its sources in Brodwino (another district of Sopot). Walking along its trail, we looked for places where it flows underground and could potentially be exposed to the surface, learning about the history of this stream and the districts through which it flows. We ended the walk at the Swelina river to see what the river might look like in its natural state.

Guide: Rafał Kubiś, Head of PTTK in Sopot

Water as a Connector – Creative Workshops on Water and Stream Renaturation in Sopot

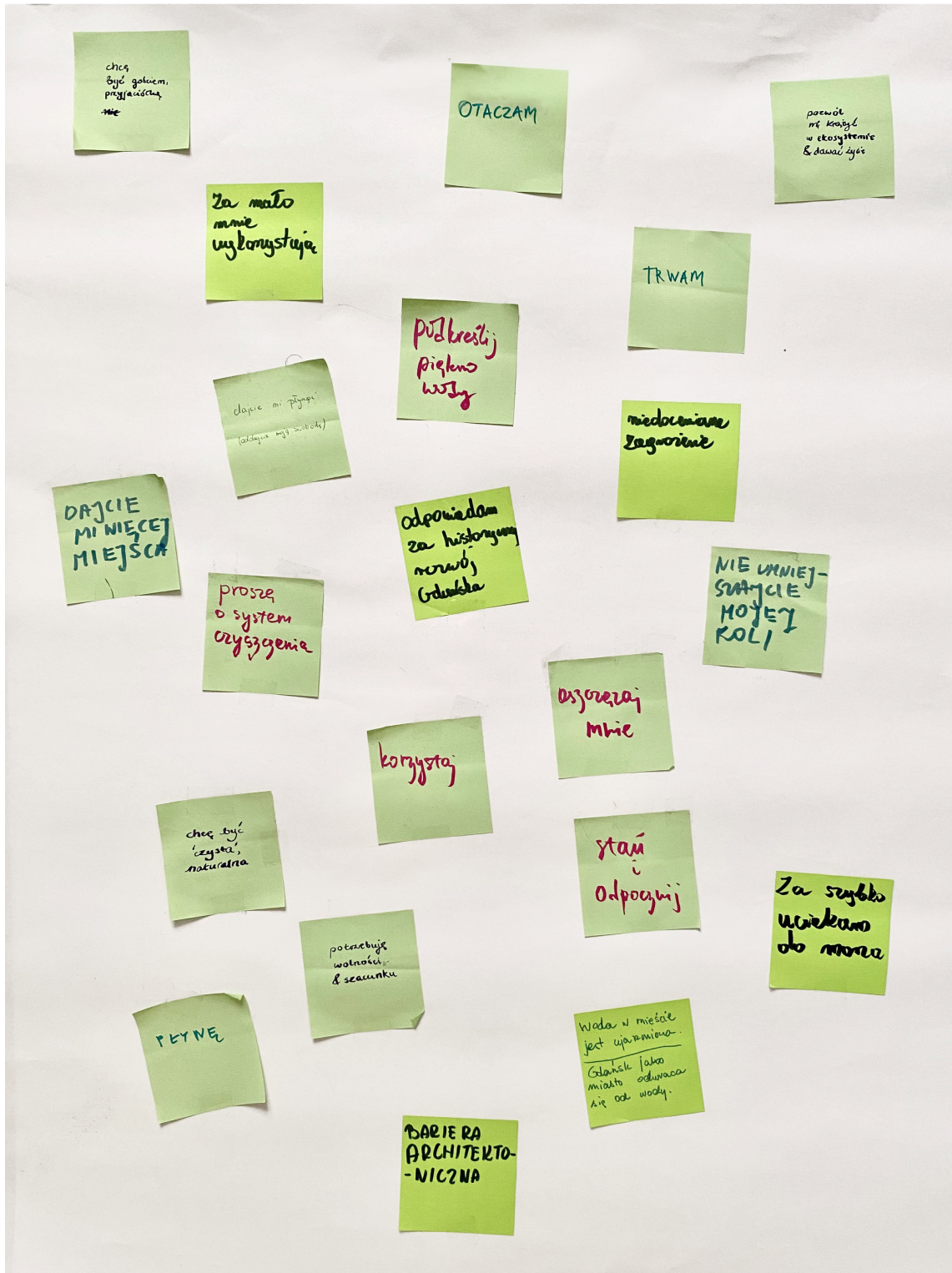

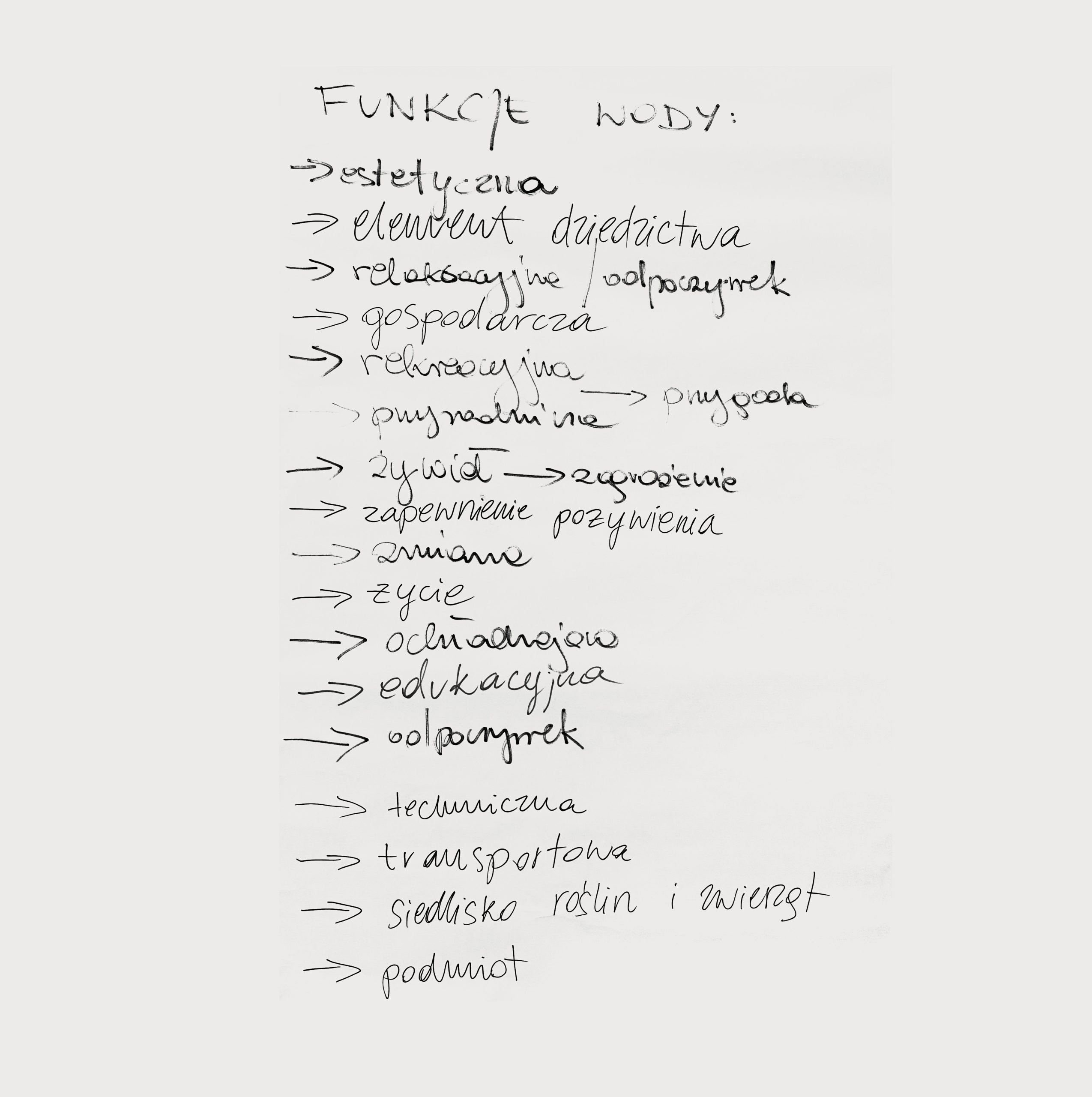

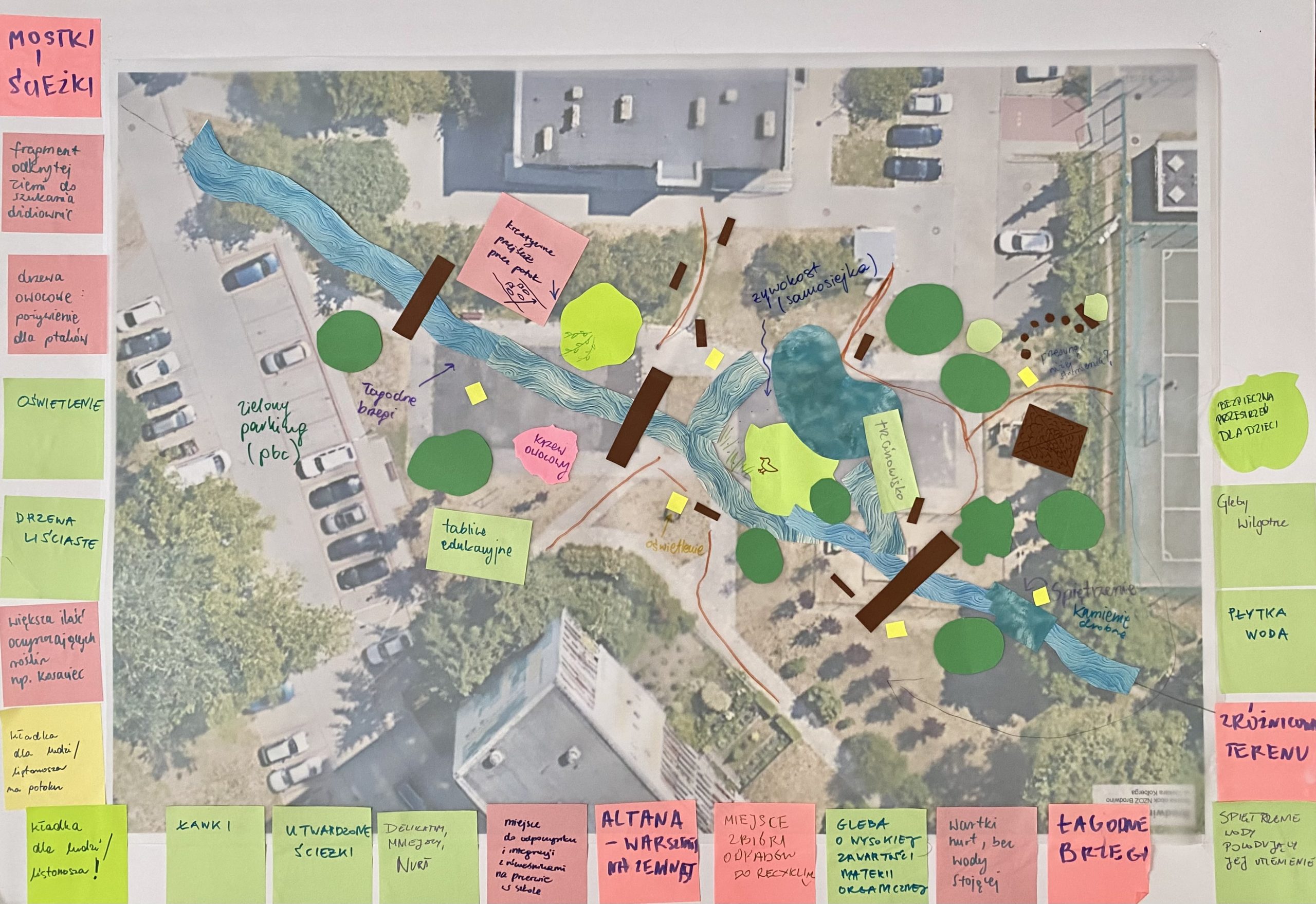

During the workshops, together with the participants and the hosts – Agata Biernacik and Kasia Świstek – we delved into the topic of our relationships with water. The meeting began with a special screening of a short, inspiring film. We focused on water in the urban context, its future and its role in shaping common spaces. The second part of the meeting was devoted to creative workshops, during which we imagined together how selected fragments of Kamienny Potok in Sopot could change after being exposed to the light of day, using information collected during an earlier guided walk. By integrating the methods of cultural mapping, mind maps and role play simulations, we searched for sustainable and creative solutions. The result were maps that I used in the final stage of the residency to create an animation about the places discussed.

Experts invited to the workshops

Agata Biernacik – the co-founder of the PLONY Foundation and the community garden at Gdańsk’s Imperial Shipyard. A graduate of the Faculty of Architecture at the Gdańsk University of Technology, she works at the intersection of urban space, ecology, and local communities. Her work focuses on promoting sustainable development, fostering social competence, and supporting the creation of shared urban spaces.

Katarzyna Świstek – a landscape architect dedicated to harnessing rainwater to enhance quality of life. Known among friends as a guide to nature’s wonders, she designs landscapes with deep respect for natural habitats. She has co-designed numerous rain garden projects in Gdańsk. Katarzyna is a graduate of the University of Life Sciences in Poznań and the Academy of Fine Arts in Łódź

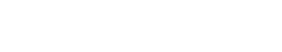

As a method for conducting the creative part of the workshop, we chose a combination of role-play and mind mapping. We prepared several character cards that described human and non-human characters, such as: a clinic patient, a 12-year-old boy, a local guide, a creative soul, a postman; and also: willow thickets, tadpoles, iris, comfrey, marsh marigold etc. Each character card had a description of the most important features, special powers (skills) and challenges (factors threatening them). Each participant drew a card of a given character and, taking on the role of that character, entered into a dialogue with others, creating a vision of a daylighted stream. Satellite maps showing selected fragments of Kamienny Potok served as the background. Participants could also refer to additional information related to a given place, e.g. proximity to a clinic or kindergarten, average age of local residents.

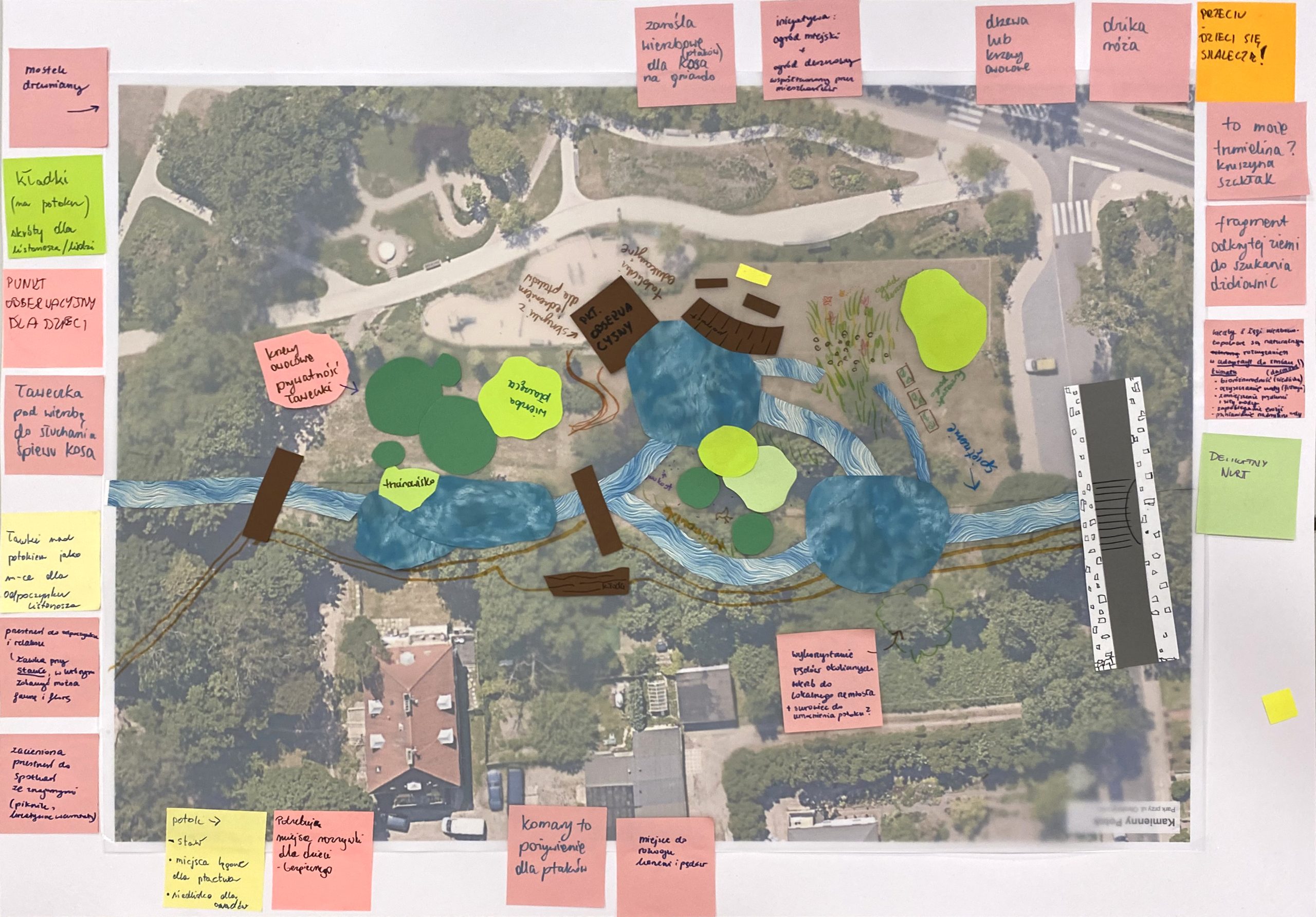

Place 1: Park at Obodrzyńców Street (Sopot Kamienny Potok)

The first place where Kamienny Potok flows underground, and could potentially be daylighted, is a green square on Obodrzyńców Street, near a city train station.

In this place, Kamienny Potok once flowed in an open bed, creating ponds. In the 1980s, these ponds were filled in and the stream was canalized.

During the workshops, interesting ideas emerged on how these ponds and the stream could be restored, including: an observation point for children, an island for wildlife, bridges and benches, a reed bed, fruit bushes, space for a city garden / rain garden.

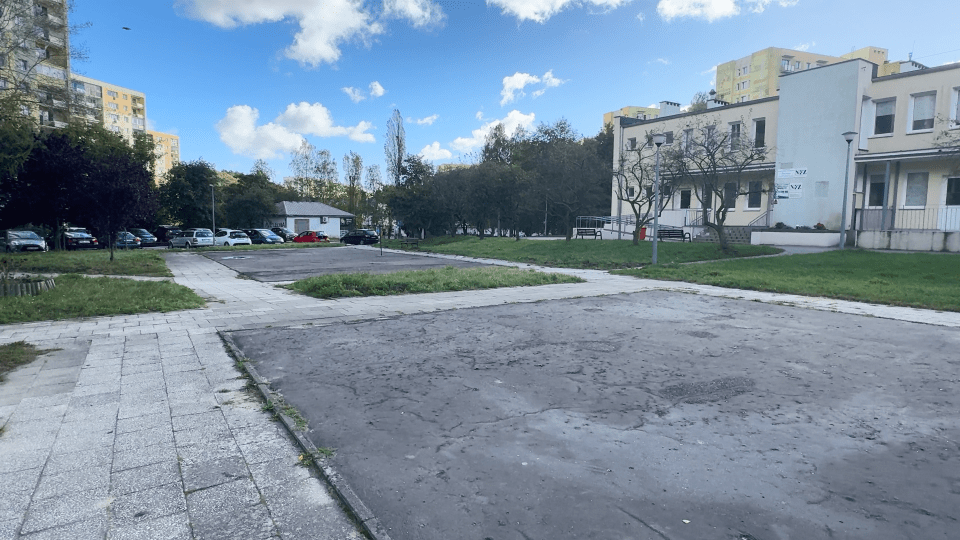

Place 2: Asphalt fields near the clinic (Sopot Brodwino)

In the upper reaches of the Kamienny Potok, there is a place where it flows between the blocks, channeled under the surface of the ground. On the surface there are two small, asphalt playing fields, which are currently unused – a new complex of sport fields and a skate park has been built nearby. Exposing this stream to the light of day would be beneficial for children, patients of the clinic and for residents of the surrounding blocks. Participants came up with many ideas for bringing this space back to life, such as: comfortable paths and benches for patients of the clinic, cleansing plants, fruit trees, lighting for safety, a gazebo for workshops and meetings, a river with gentle banks, which is not too deep and has a fast current, shrubs with beautiful scents serving as a sensory relief.

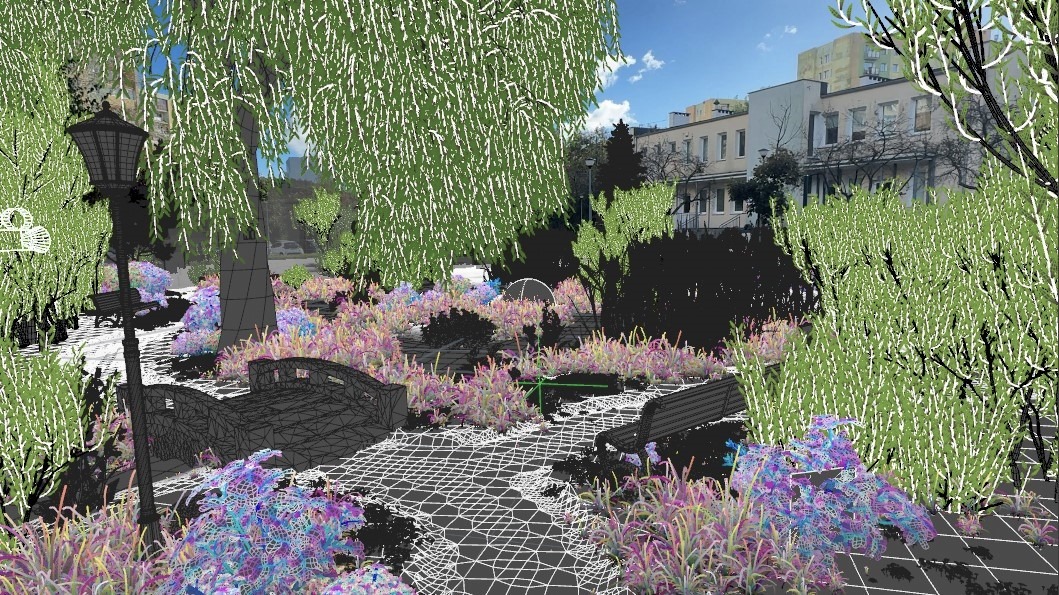

The final stage of the project involved creating two 3D animations envisioning how the selected fragments of Kamienny Potok might appear after being uncovered. These designs incorporated insights and ideas gathered from participants in earlier workshops. By employing the camera tracking method, I integrated the animations with real-world footage and enhanced the experience with a sound composition for added immersion. Each animation begins and ends by contrasting the envisioned transformation with the site’s current state.

Place 1: Park at Obodrzyńców Street (Sopot Kamienny Potok)

The park, previously a modest green space, underwent a transformation into a vibrant oasis that supports a wide variety of plant and animal species, while also serving as an inviting retreat for relaxation and recreation by the water. The riverbed was carefully reshaped to include parallel sections, creating a dynamic flow that occasionally widens into serene ponds. These ponds became thriving habitats for aquatic life, such as the common minnow, and a sanctuary for birds, including ducks and blackbirds. To enhance the experience for visitors, thoughtful installations were introduced, such as an elevated observation footbridge that offers views of the area and a natural pathway made from tree stumps, designed to blend seamlessly into the environment and encourage exploration and play.

Place 2: Asphalt fields near the clinic (Sopot Brodwino)

After removing vast stretches of old asphalt, a lively, fast-flowing stream was uncovered, transforming the landscape into a haven for wildlife. The stream now forms a small island that attracts wild birds, alongside a shallow lake fringed with reeds, marsh marigolds, and comfrey. A weathered wooden log was intentionally placed by the stream to serve as an educational feature, illustrating the natural biological processes at work. A majestic willow tree offers shade and shelter for both people and animals, thriving in its water-rich surroundings. Thoughtfully designed paths and benches ensure accessibility for visitors of all ages, while nearby wild rose bushes enhance the environment with their soothing fragrance, offering therapeutic benefits to patients at the neighboring clinic.

• Water is the thread that weaves through our landscapes, binding ecosystems together. It serves as both a literal and symbolic connector, creating shared spaces where diverse forms of life, including humans, converge. Urban streams and waterways also serve as vital links to our cultural and historical heritage.

• Participants in the project, residents of the Tri-City area, aspire to influence changes in their city’s water infrastructure. However, many feel uncertain about how to make their voices heard effectively.

• During the workshops, it became evident that water evokes deep emotional connections for many people, stirring personal memories and diverse associations.

• Historically, many streams were buried underground at a time when their value was seen purely in utilitarian terms, and understanding of ecosystems was limited. Today, we have both the knowledge and the tools to restore many of these streams to their natural state. However, achieving this requires engaging the community. Showing that change is achievable and helping residents imagine a better future – through tools like animation – can inspire action.

• In designing shared spaces, such as a daylighted stream, balancing the needs of humans with those of plants and animals can be challenging. By considering all perspectives and seeking compromises, it is possible to create a harmonious ecosystem that benefits everyone.